The Age: Half of Australians on financial brink as living costs bite

Managing employee retention in a post-pandemic world Employee retention requires intentional steps to keep employees engaged and focused so they choose to stay on the job.

Employees are leaving jobs in unprecented droves.

Employers can scarcely afford to lose good people, let alone in such a tight labour market.Why are employees leaving? The dangers of losing top talent, and what organisations can do about it.

“I noticed that the dynamic range between what an average person could accomplish and what the best person could accomplish was 50 or 100 to 1. Given that, you’re well advised to go after the cream of the cream. A small team of A+ players can run circles around a giant team of B and C players.”

Steve Jobs

The last year has seen a tidal wave of resignations around the world and “The Great Resignation” has become an increasingly maligned term among human resources and senior management professionals.

Also known as the “Big Quit”, the Great Resignation has seen unprecedented numbers of employees leaving their jobs in the wake of the Covid pandemic.

Research suggests that lockdownsand work-from-home measures – amongst other changes forced by Covid – has caused workers to rethink careers, work-life balance and long-term goals. This occurs just as the economy re-opens and demand for labour surges in Australia.

According to a report by NAB, which surveyed 2000 Australians, 1 in 5 employees have changed jobs in the past year and 1 in 4 consider leaving their current employment(1).

The highest resignation rate was among unskilled workers at 37%, followed by IT and technology workers at 28%.

For businesses, IT workers, managers and sales force are amongst the hardest roles to fill and cause the most disruption to a business when employees resign.

Studies suggest that the cost of replacing these types of workers is around 150% of their annual salary.

The loss of these types of employees also creates a second-order effect. The best people in a business are the ones most likely to be tempted away, and are the ones who have the greatest alternative opportunities.

According to a report by NAB, which surveyed 2000 Australians, 1 in 5 employees have changed jobs in the past year and 1 in 4 consider leaving their current employment(1).

The highest resignation rate was among unskilled workers at 37%, followed by IT and technology workers at 28%.

For businesses, IT workers, managers and sales force are amongst the hardest roles to fill and cause the most disruption to a business when employees resign. Studies suggest that the cost of replacing these types of workers is around 150% of their annual salary. The loss of these types of employees also creates a second-order effect. The best people in a business are the ones most likely to be tempted away, and are the ones who have the greatest alternative opportunities.

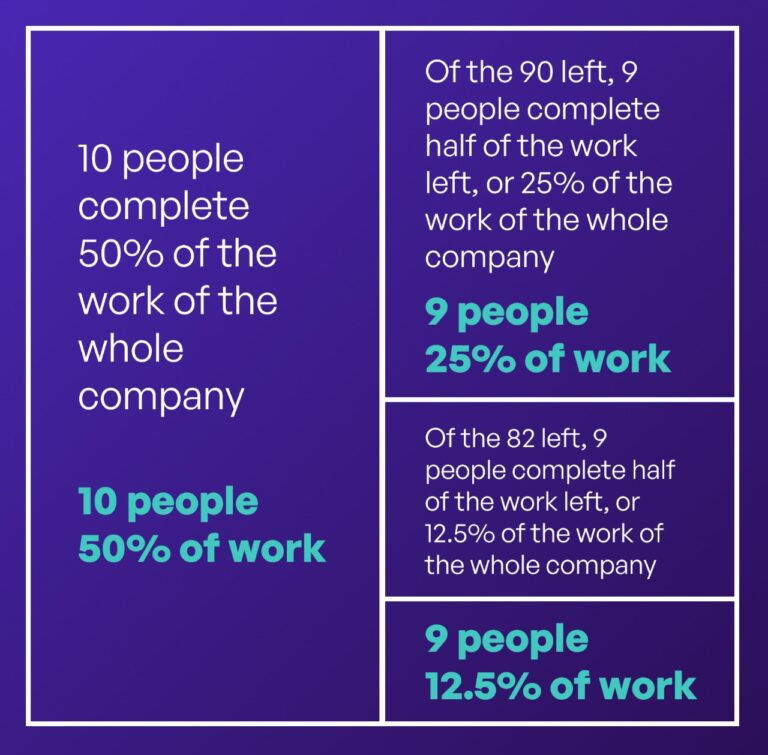

Price’s Law, derived from the Pareto Principle and described by physicist and social scientist Derek de Solla Price, suggests that in creative fields a small number of people are responsible for 50% of the work done. He noticed that the same handful of people dominate publications within a niche subject, and then researched this across other creative domains.

Solla Price suggests that the square root of the number of people in a field create 50% of the output. That means that in a company of 1000 people, 33 are responsible for half of the creative work. Losing 30 people may not seem like much in a company with 1,000 people, but the consequences can be catastrophic if they are these key people, and they can’t be replaced.

Price’s law shows how creative work is produced in a 100-person company.

10 staff do 50% of the work. (5% each)

9 people do 25% of the work. (2.87% each)

9 people do 12.5% of the work. (1.39% each)

72 people do 12.5% of the work, or 0.17% each.

A person from the top group, completes 30 times more creative work than a person in the bottom group.

Many senior leaders have experienced the devastating effects of a key person leaving. IT projects slow or derail, business momentum, sales or both grind to a halt, organizational culture sags, and the absence of inspirational leaders and mentors leaves more junior staff despondent and directionless.

The impact of Price’s Law can have serious adverse effects on companies that are prone to fast-changing technology or that are working on large projects. And the world gets faster and more complex every year. Many businesses are critically dependent on the work done by a handful of irreplaceable people. Owners must do what they can to identify them and keep them engaged.

When key people leave, new people take time to integrate into the company. This puts extra pressure on the other members of the team – which is made all the worse if there’s a time gap between the old person leaving and a new one starting. The result is that other people will become can become more inclined to leave, and a team can collapse from the middle with the loss of key employees.

Price’s Law predicts that ineffectiveness grows exponentially, whereas competence grows linearly. It is imperative, therefore, to identify the top performers in organizations. And it is imperative that they don’t leave, as they add disproportionate value.

For managers and leaders, the loss of key performers puts extraordinary strain on you, your team and the whole organisation. When these key performers are replaced, they must learn the new role and organisation, and there’s a good chance that they won’t have the same level of output as their predecessor.

A question that leaders must ask themselves is twofold:

1.How do I keep the top people in the organisation?

2.What is the contribution of the bottom people in the organisation, and should they be retained?

The information above might suggest that employers should just focus on key senior people. Unfortunately, Price’s Law applies to people in creative domains: technology, marketing, user experience, and management.

But organisations need many front-line employees, who don’t work creatively, but who often interface with customers and suppliers, or allow an organization to scale its external face. These are cleaners, retail workers, factory workers, administration staff and operations employees. As outlined above, a third of these employees have left work in the last year.

Australia faces a particular challenge for these employees. In March 2020, there were 494,000 international students living in the country. By October 2021 that number was 263,000 (2).

International students working in Australia provided a symbiotic benefit: students could earn money while they studied, helping offset the cost of pursuing a degree in Australia, and businesses had a supply of employees to fill frontline lower skilled roles (which is not to suggest that these students lacked skills – rather, they worked in these types of roles to support attainment of academic objectives).

The reduction of students entering the country has halved this valuable employment lubricant.

The visible effect of this has been obvious: Cafes and restaurants have been forced to reduce hours and childcare centres have closed their services, and retail businesses are constantly short-staffed.

The less visible effect is that managers are forced to complete work usually handled by less senior staff and senior IT people are forced to fix simple technology issues and executives across businesses are burdened by increasing workloads, often filled with chores they’d left years ago, increasing their stress, dissatisfaction, and burnout.

The resignation risk of Price’s precious few increases.

A multitude of other forces also drive employees to resign. Economic causes include wage stagnation, rising costs of living, and perceived freedom provided by Covid-19 stimulus payments.

Organisational and psychological factors such as long-term job dissatisfaction also play a part.

Research reports in MIT Sloan Management Review found a toxic corporate culture was the leading predictor of employee turnover during The Great Resignation. Job insecurity and failure to recognize employee performance also made the list.

But interestingly, research suggests that 80% of voluntary resignations could have been prevented, so it is not all misery for businesses seeking to keep their employees on board (3).

NAB’s analysis found that these high resignation rates are not translating into more money in the hands of employees. But, as banking executive Julie Rynski told The Age, it is pushing companies to rethink the benefits they have on offer. She also said pay is not the biggest contributor to changing jobs.

What can Employers do to Attract and Retain Talent?

Frank Breitling, a partner in BCG’s New York office analysed 800,000 data points collected over 20 years indicating what people value at work and reported it in the Harvard Business Review(4).

He suggests companies need to get on the same page with employees by reconceptualizing what it means to be part of their organization. Responses from both white- and blue-collar workers in range of industries, fit four broad categories: value, purpose, certainty, and belonging.

He goes on to suggest six measures that have the greatest impact:

1. Incentivize loyalty: pay people enough to take money off the table and offer bonuses

2. Provide opportunities to grow: help people shape their careers to increase employee engagement

3. Elevate your purpose: communicate and activate your purpose

4. Prioritize culture and connection: Build and solidify relationships with your coworkers and staff

5. Invest in taking care of your employees and their families: Offer incentives to the families of staff

6. Embrace flexibility: Provide flexibility to employees around their time and money

NAB’s data indicates the need for employers to rethink how they can further support staff, even if they don’t have huge budgets for pay rises. Employers have initiated innovative approaches over the past 12 months, such as pandemic leave, mental health days, additional training and development opportunities.

And employers are successfully addressing their benefits and workplace cultures to retain and attract staff.

They are getting creative on leave entitlements, and they’re working hard to address poor management, staff exhaustion and the need to promote inclusion and real flexibility.

Improving employee engagement can help retain key people, and retaining top talent is key to promoting organizational growth, while recruiting and retaining new employees is expensive and time consuming.

Tom Jamieson is COO at oNesto, a digital rewards and recognition platform based in Melbourne, Australia. He has 20 years experience in technology, and holds a Masters in Management from Harvard University.

Managing employee retention in a post-pandemic world Employee retention requires intentional steps to keep employees engaged and focused so they choose to stay on the job.

Managing employee retention in a post-pandemic world Employee retention requires intentional steps to keep employees engaged and focused so they choose to stay on the job.

Managing employee retention in a post-pandemic world Employee retention requires intentional steps to keep employees engaged and focused so they choose to stay on the job.

Managing employee retention in a post-pandemic world Employee retention requires intentional steps to keep employees engaged and focused so they choose to stay on the job.

Managing employee retention in a post-pandemic world Employee retention requires intentional steps to keep employees engaged and focused so they choose to stay on the job.

More and more employers are looking for ways to help their employees save money on their shopping. oNesto solves this.